Owl monitoring took place during nineteen nights between 13 September and 2 November 2002, at Rocky Point Bird Observatory. Owl monitoring was conducted by recording owl detections (vocalizations and sightings) and by the capturing and banding of owls. Owls were captured using three to six mist nets in conjunction with an audiolure, and a bal-chatri trap was also employed. Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus) were detected each night and at least four Great Horned Owls were present on 5 October. Barred Owls (Strix varia) were also recorded each night of monitoring, with at least three recorded on the 12 October. Two Barred Owls were caught in the mist nets and one was caught in the bal-chatri trap. The remains of two other Barred Owls found during the day, brings the total number of Barred Owls to at least five. Northern pygmy-owl (Glaucidium gnoma), Western Screech-owl (Otus kennicottii) and Barn Owl (Tyto alba) were not detected during the night monitoring, but a Northern Pygmy-owl was banded during day-time passerine banding on 18 September, and the remains of a Barn Owl were found during the day on 20 September; Western Screech-owl was not recorded in 2002 at Rocky Point. The number of Northern Saw-whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) captured in the mist nets and banded was 210. The capture rate for Northern Saw-whet Owls was 1.59 owls/hour and 0.32 owls/net hour. The peak of Northern Saw-whet Owl movement occurred between the 11 and 12 of October, with 38 and 25 captured respectively. The age of Northern Saw-whet Owls was determined by plumage; 72% were hatch years, 21% were second year and 7% were after second year. The sex of the Northern Saw-whet Owls was determined by morphometric measurements (mass and wing cord); 15% were male, 44% were female and 40% could not be assigned a sex. Eight of the 210 Northern saw-whet Owls were recaptured, with the mean period between capture/recapture being 4 hr 40 min., the longest period was16 hours. Capture rates of Northern Saw-whet Owls were highest in the nets closest to the audiolure, with the closest net capturing 48% of the Northern Saw-whet Owls. The majority (59.8%) of Northern Saw-whet Owls were captured in the first six hours of a given evening. All of the Northern Saw-whet Owls banded appeared to be A. a. acadicus; the subspecies A. a. brooksi, endemic to the Queen Charlotte Islands was not observed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Results |

Discussion |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Northern Saw-whet Owls banded per evening during the fall of 2002. |

| Figure 2. Northern Saw-whet Owls banded per evening verse capture effort per evening. |

| Figure 3. Age class distribution of Northern Saw-whet Owls banded at Rocky Point Bird Observatory, fall 2002. |

| Figure 4. Sex ratio of Northern Saw-whet Owls banded at Rocky Point Bird Observatory, fall 2002. |

| Figure 5. Percentage of Northern Saw-whet Owls captured by each of the six nets. |

| Figure 6. Locations of the six mist nets relative to the audiolure. |

| Figure 7. Museum skins of Northern Saw-whet Owl subspecies, Aegolius acadicus acadicus and Aegolius acadicus brooksi. |

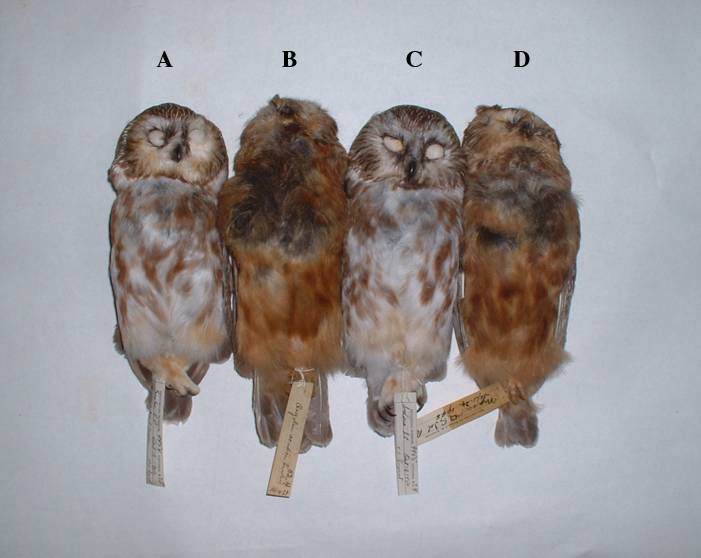

| Figure 8. Skin specimens of Aegolius acadicus acadicus and Aegolius acadicus brooksi. |

| Figure 9. Ventral (A) and Dorsal (B) views of Aegolius acadicus brooksi. |

|

| Table 1. Known stopover times of Northern Saw-whet Owls at Rocky Point Bird Observatory, fall 2002. |

| Table 2. Percentage of Northern Saw-whet Owls captured in the first 4-8 hours after the end of daylight. |

| Table 3. Occurrences of Northern Saw-whet Owls banded during daytime passerine banding at Rocky Point Bird Observatory between 1994 and 2002 |

The area of land known as Rocky Point on the southern tip of Vancouver Island was identified as a suitable site for monitoring fall movements of neotropical passerines and diurnal raptors in the early nineties. A group of volunteers and the Canadian Wildlife Service approached the Department of National Defence (DND) who manages the property as Canadian Forces Base, Ammunition Depot CFAD Rocky Point. The DND was receptive to a proposed monitoring project, and bird banding began in 1994. Rocky Point’s geographic location has proven to be an excellent funnel for concentrating migrating birds. Rocky Point Bird Observatory (RPBO) now bands over 3,000 birds annually and since 1994 has banded over 19,000 individuals, of some 90 species.

Since 1994, it has become apparent that a fall concentration of owls occurs at RPBO, with six species of owls being regularly observed: Barn Owl (Tyto alba), Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), Barred Owl (Strix varia), Western Screech-owl (Otus kennicottii), Northern Pygmy-owl (Glaucidium gnoma), and Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus). Barred Owls and a Northern Pygmy-owl have been banded during the daytime passerine banding, but the most notable influx of these owl species is the Northern Saw-whet Owl, with 11 being caught during the day between 1994-2001 (Derbyshire 1999, Derbyshire 2000a, Gibson 2001, RPBO data). The Northern Saw-whet Owl is migratory in eastern North America (Cannings 1993), but information regarding annual movements of this species in British Columbia is virtually non-existent (Campbell et al. 1990, Cannings 1993).

Owl populations on Vancouver Island have become a conservation and management concern in recent years due to habitat loss through urban development and industrial forestry, and the general paucity of available biological information. This concern has initiated a number of recent owl inventory projects on Vancouver Island: Clayoquot Sound (Ross and Eggen 1997) the Nimpkish Valley (Setterington 1998), the Beaver Lodge Lands (Manley 1999), sub alpine areas near Woss (Joy et al. 1999) and the Campbell River Watershed (Mico and Van Enter 2000, Pendergast 2002). The British Columbia Nocturnal Owl Survey, part of a national volunteer owl monitoring program run by Bird Studies Canada, is conducting ongoing province wide owl inventories, including work on Vancouver Island (Bird Studies Canada 2002)

Given the need for information on owl populations and the concentration of owls during the fall at RPBO, it was decided to initiate an owl monitoring program at RPBO. The purpose of the project is two-fold. 1) To collect biological information regarding owls on Vancouver Island and to make this information available to resource managers, ornithologists and the public. This information will include the number of owls, the species and subspecies, moving through southern Vancouver Island, the chronology of these movements; population parameters including annual reproductive success, longevity and long-term population fluctuations. 2) The project’s final purpose is to heighten public awareness of conservation issues concerning owls and to foster public stewardship of our avian resources through providing volunteers with hands on experiences with these cryptic and charismatic species.

Based on the occurrence of owls at RPBO in previous years, owl monitoring was conducted from mid-September to the end of October (Derbyshire 1999, 2000a, Gibson 2001), on Friday and Saturday evenings. Owl monitoring was conducted by recording the direction of owl vocalizations and sightings, and by capturing and banding owls. Monitoring began at dusk and ended one hour before first light the following morning. The end and start of daylight was determined by Sunrise/Sunset tables, computed by the National Research Council, Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics in Victoria.

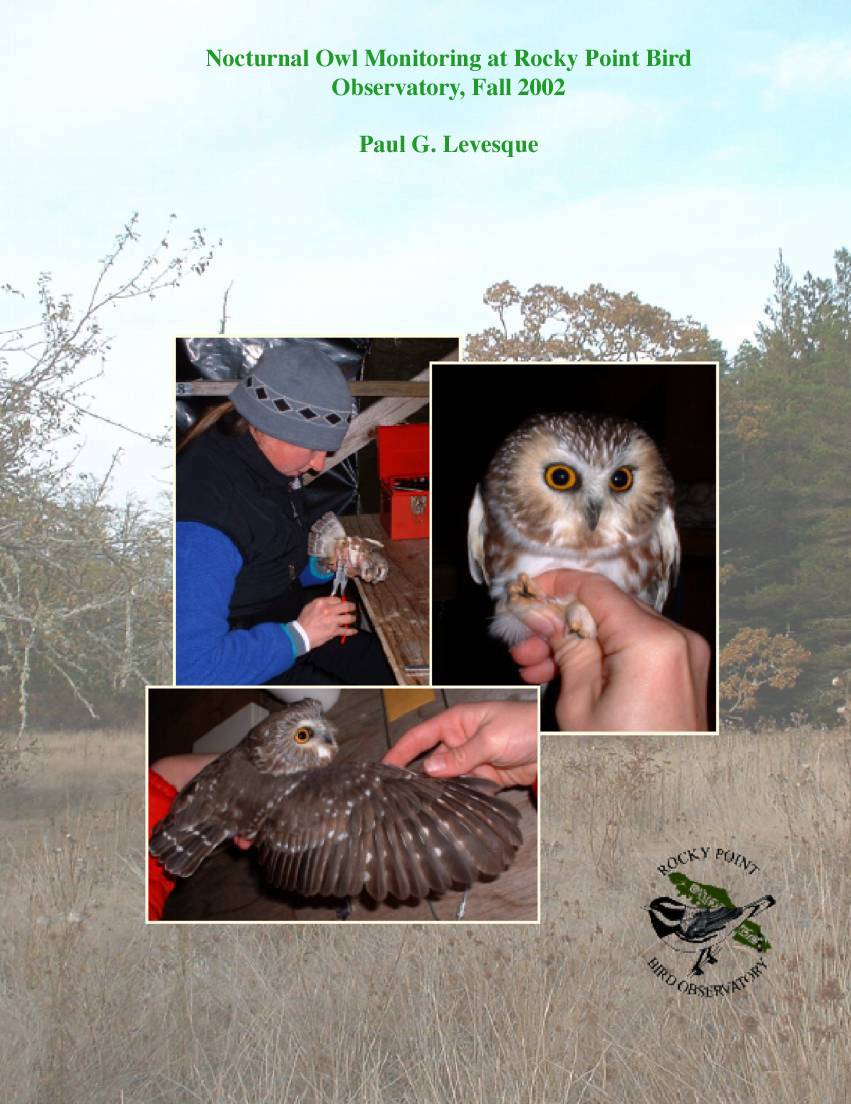

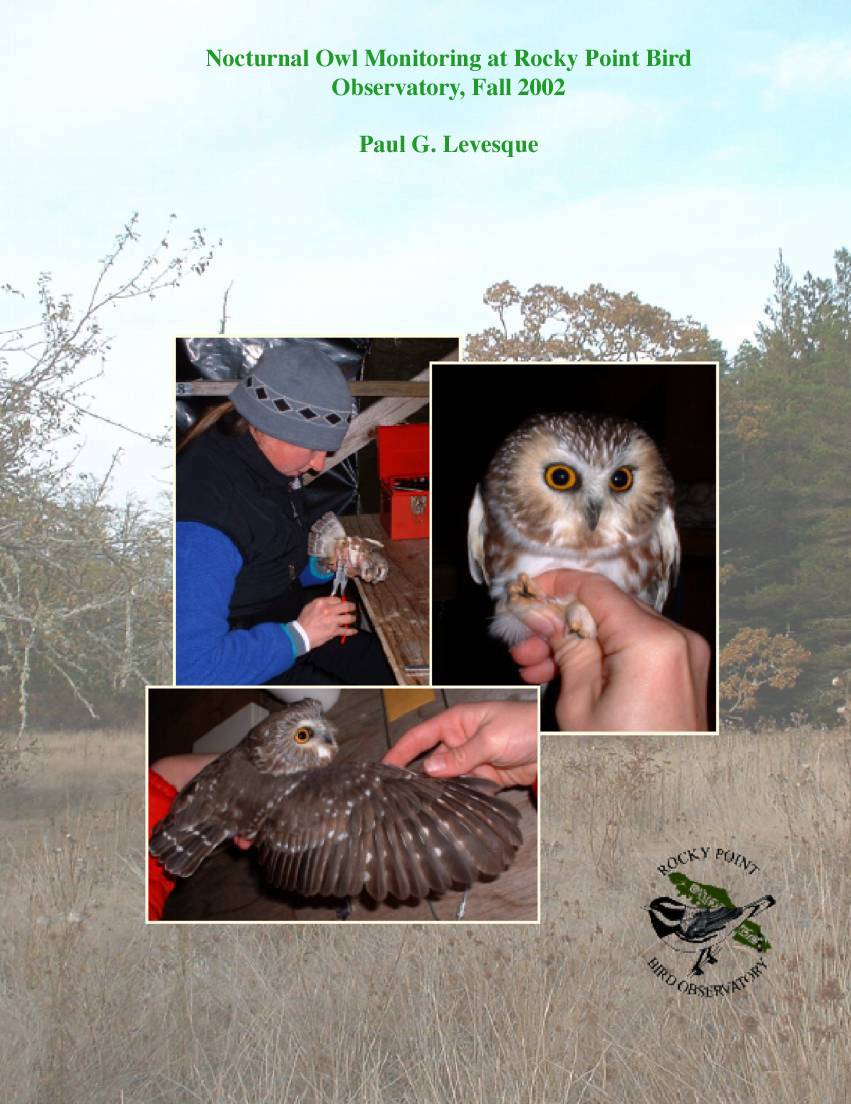

The owl trapping was based on methods employed by other researchers and bird observatories in North America (Erdman and Brinker 1997, Erdman et al, 1997 and Project Owlnet 2002). Between three and six nets were placed around an audiolure, so that owls approaching the lure would become entangled (a general schematic of the net configuration can be seen in Fig. 5 in Appendix I). The nets used were 12 m x 2.6 m, with a 60 mm mesh size. The audiolure consisted of an automotive compact disk player (Sony CDX-L300, 45 Watt x 4 output) and speaker (Alpine 6 x 9, 100W) broadcasting the Northern Saw-whet Owl solicitation call. The solicitation call was broadcasted at a volume that could be heard over 400 m away by human observers. In an effort to capture the larger owl species, a baited bal-chatri trap (Bloom 1987) was used near the net set up and in known flight corridors as potential trapping opportunities arose.

The handling and banding of owls followed the applicable sections of the RPBO banding protocol (Derbyshire 2000b); these sections stipulate the safe handling and banding of birds, and the training and supervision of volunteers. Monitoring was terminated in poor weather conditions; winds exceeding 15 km/hr or precipitation. Owls were banded with aluminum US Fish and Wildlife bands on their right leg. Mass and a series of morphometric measurements were recorded: exposed culmen, wing cord and standard tail length. In addition to these measurements, each owl’s crop was examined for the presence of food; the state of the pectoral muscle relative to the keel was scored on a scale of 1-5 as an index of body condition, and eye colour was recorded. Age was determined by examining molt patterns of primary and secondary feathers according to Evans and Rosenfield (1987), Pyle (1997) and Project Owlnet (2002). Molt patterns on the wings were recorded for all Second Year and older individuals. The sex of Northern Saw-whet Owls was determined by a discriminant function analysis of mass and wing cord (Brinker et. al 1997, Project Owlnet 2002).

The Rocky Point Bird Observatory is situated on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, British Columbia (48° 19.15¢ N 123° 32.47¢ W) and is the most southern point in the province. The habitat at the site consists of a mosaic of mature fields, early to late succession coniferous forests, dense riparian and Garry oak parklands. The area immediate (>30m) to the nets was an early succession (~ 35 years old) stand of Grand Fir (Abies grandis) and Shore Pine (Pinus contorta). This stand of trees had a high degree of canopy closure, with a complete absence of shrub or herb layers.

Monitoring was conducted during 19 nights between 13 September and 2 November. Three species of owls were regularly observed through this period, Great Horned Owl, Barred Owl and Northern Saw-whet Owl. During this period the nets were open for a total of 132.1 hr., making up 652.2 net hr. Of the 19 nights of monitoring, 12 were full nights, starting at dusk and ending an hour before first light. Monitoring was cut short due to weather on the 14 and 28 of September; the 13, 20, 26 September and 3 October were partial nights due to prior commitments of the banders and the 13 October was cut short by the presence of predators at the nets. Monitoring was hampered on the 18 and 19 October by heavy fog that covered most of coastal British Columbia. On these evenings, all of the owls recorded and banded were before approximately 22:00 when the fog moved on to land.

Barn Owls were not recorded during the nocturnal monitoring. However, the remains of a Barn Owl were found on 20 September during the day. This Barn Owl was aged as a hatch year and the cause of death appeared to be the result of avian predation. On the morning of 14 October a Barn Owl was observed three kilometers north of the study site, this observation brings the total of Barn Owls in the area to two.

Great Horned Owls were heard and seen during each evening of monitoring. A minimum of four individuals were recorded on 5 October. Also recorded most evenings until the 26 October, was a begging juvenile Great Horned Owl. Adult Great Horned Owls did not appear to be attracted to the nets by the audiolure, however on two evenings a juvenile perched in the upper canopy above the nets and made begging calls for up to two hours.

Barred Owls were heard vocalizing on each night of monitoring, with a high count of three individuals on the evening of 12 October. Barred Owls were attracted to the nets by the audiolure, resulting in two captures on 18 October and 1 November. In an effort to target Barred Owls, a bal-chatri trap was employed. The bal-chatri trap caught a Barred Owl in the morning of the 18 October; this hatch year bird was recaptured with the bal-chatri trap in the afternoon on 2 November.

The remains of two Barred Owls were found in the study area, one on 27 September and another on 2 October. Both of the dead Barred Owls appeared to be the result of avian predation. With two predated Barred Owls and three Barred Owls banded, at least five individuals were present at Rocky Point during the fall.

Although recorded at RPBO and thought to breed at the site (RPBO data) Western Screech-owls were not detected during evening monitoring or during the day.

Northern Pygmy-owls were not recorded during the nocturnal monitoring. One Northern Pygmy-Owl was banded during daytime passerine banding on 18 September. A Northern Pygmy-owl was seen on the morning of 23 September, but it is unknown if this was the same owl banded five days earlier.

On the 13 September, one Northern Saw-whet Owl was banded (Fig. 1), but detections of vocalizations suggested two other Northern Saw-whet Owls were in the area. The following evening, monitoring was stopped due to increasingly strong winds. On the evening of the 20 September, 11 Northern Saw-whet Owls were banded. The recording of Northern Saw-whet Owl vocalizations on 20 September underestimated the number of this species in the area, although 11 Northern Saw-whet Owls were banded, overlapping calls suggested a high count of only four individuals in the area. On 27 September, 23 Northern Saw-whets were banded; this evening had the third highest volume of the project. The following evening monitoring was curtailed due to rain. The following weekend 27 Northern Saw-whet Owls were banded, with 16 on 4 October and 11 on 5 October.

The peak in Northern Saw-whet Owl movement occurred during the evenings of the 11, 12 and 13 October, with 38, 25 and 10 banded respectively (Fig. 1). The 73 Northern Saw-whet Owls banded during this three day period represent 35% of the total owls banded on the project. It is likely that the number Northern Saw-whet Owls banded on the 13 October would have been higher if not for the presence of a Barred Owl at the nets, by midnight it was apparent that this individual was actively hunting and it was decided to close the nets.

The number of Northern Saw-whet Owls banded on 18 and 19 October was considerably lower than the previous weekends (Fig. 1). The weather had changed during the week and the predominately clear skies were replaced with a heavy fog bank. The fog bank moved inland in the evenings and effectively halted owl captures and vocalizations. On the 18 October, the nets were closed for two hours due to a Barred Owl and once the nets were reopened, a Black Tailed Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) became entangled in net 6; the net was destroyed. Clear skies returned for the final two weekends of monitoring and banding totals and detections increased. During the 25 and 26 October, 24 Northern Saw-whet Owls were banded. 1 November, 18 Northern Saw-whet Owls were banded, followed by 10 banded on 2 November.

Although the sample size for adult Northern Saw-whet Owls (SY and ASY) is relatively small, there did not appear to be a differential timing in the movements of juvenile and adult Northern Saw-whet Owls (Fig 1).

The information presented in Figure 1 should be put into a context of trapping effort. The owl monitoring project was a pilot project, therefore there was considerable variation in the number of nets opened on a given evening and variation in the amount of time nets were open on a given evening. When the number net hours are compared to the evening banding totals (Fig. 2) some degree in the variable nightly banding totals can be explained.

Figure 1. Banding results of Northern Saw-whet Owls per evening during the fall of 2002. Totals of Northern Saw-whet Owls per evening have been separated into three age classes: ASY is After Second Year birds that are at least two years of age; AHY refers to After Hatch Year birds that are at least one year of age; and HY refers to Hatch Year birds which are young of the year. NSWO = Northern Saw-whet Owl.

Figure 2. Northern Saw-whet Owls banded per evening versus capture effort per evening. Capture effort is expressed in net hours, where the number of open nets is multiplied by the time each net is open. NSWO = Northern Saw-whet Owl.

The monitoring project resulted in 210 Northern Saw-whet Owls banded. The overall capture rate for the project was 1.59 Northern Saw-whet Owls per hour of operation, and the capture rate per net hour was 0.322. Of the 210 Northern Saw-whet Owls banded, 151(72%) were aged as Hatch Year (HY), 44 (21%) were aged as Second Year (SY) and 15 (7%) were aged as After Second Year (ASY) (Fig.3)

Sex determination of Northern Saw-whet Owls was based on mass and wing cord measurements. Females made up the majority of the Northern Saw-whet Owls 93 (44%) and males 32 (15%) (Fig. 4). There is overlap in the mass and wing cord measurements of male and female Northern Saw-whet Owls, individuals with measurements that fell into the overlap could not to be described as male or female and were reported as "unknown sex" (Fig. 4). The portion of unknown sex Northern Saw-whet Owls was 40%. (85) of the total. The sex ratio of male to female to unknown sex was 1: 2.9: 2.6.

Figure 3. Age class distribution of Northern Saw-whet Owls banded at Rocky Point during fall 2002. HY refers to Hatch Year, these owls were hatched in the spring of 2002; SY refers to Second Year, these owls were hatched in the spring of 2001; ASY refers to After Second Year, these owls were hatched in the spring of 2000 or at an earlier date.

Eight Northern Saw-whet Owls banded at RPBO during the fall of 2002 were recaptured during the owl monitoring project (Table 1) The time between capture and recapture ranged between 45 min. to 16 hours and the mean stopover time between capture/recapture was 4 hr. 40 min. (SD ± 4 hr. 57 min.). However, the mean stopover time includes an individual netted and banded during the day (07:30) and recaptured 16 hours later during the evening. This owl was initially released during daylight, shortly after processing and was forced to roost in the area. If this recapture is removed from the pool, the mean stopover becomes 3 hr. 2 min. (SD ± 3 hr. 50 min.). Each of the three age classes of Northern Saw-whet Owl was recaptured, with 75% of the recaptures being hatch year birds.

Table 1. Known stopover times of Northern Saw-whet Owls at Rocky Point Bird Observatory, fall 2002. The Northern Saw-whet captured on 5 October. was captured during daytime passerine banding. HY refers to Hatch Year, SY refers to Second Year, and ASY refers to After Second Year.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The portion of Northern Saw-whet Owls captured by each of the six nets varied from 1- 48% (Fig. 4). Nets 1,2,3 and 4 were open consistently, with each net being open between 121-124 hours, Nets 5 and 6 were open for 77 hours and 24 hours respectively, and hence captured fewer Northern Saw-whet Owls. Net 3 was the closest net to the audiolure (shortest distance 3 m.) and captured 48% of the 210 Northern Saw-whet Owls banded (a general schematic of the net configuration can be seen in Fig. 5 in Appendix I). On a number of net checks, Northern Saw-whet Owls were seen perched within a meter of the audiolure.

Northern Saw-whet Owls were generally captured throughout the evening. However, there was a general trend of high activity during the first 4 hours of trapping, followed by a 2-4 hour lull, then occasionally followed by an increase of activity in the last 2-3 hours of the evening. The timing of Northern Saw-whet Owl activity and subsequent captures in the nets, is important for the development of monitoring protocols and the efficient use of resources. The portion of Northern Saw-whet Owls captured in the hours after net opening is described in Table 2. These results are from the 12 full evenings of monitoring, banding results from partial evenings are not included.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although Barn Owls were present at RPBO during the fall (a sight record and a deceased bird), the owl monitoring failed to detect the presence of this species. It is curious that vocalizations of Barn Owls were not recorded during the evenings of monitoring. One explanation is that there were few Barn Owls present and by chance the owls were not detected. It is also possible that with the number of potential predators in the area, the Barn Owls were remaining silent in an attempt to avoid predation. The recovery of the Barn Owl on the 20 September 2002 is the second recovery of a predated Barn Owl, the remains of an individual were found at RPBO 23 August 2001 (Gubersky pers. comm.).

The origins of the two Barn Owls detected in the fall 2002 is unknown, they may have been local breeders; rural Metchosin and Rocky Point has suitable habitat although no nests are known in these areas. This species is regarded as relatively sedentary in coastal British Columbia (Campbell et al. 1990). There are two cases of Barn Owl band recoveries that are noteworthy. A nestling banded 4 April 1970, in Richmond was recovered on 11 December 1978, in Nanaimo on Vancouver Island (Campbell et al. 1990). This recovery was 65 km west of the banding site and this movement required crossing the Strait of Georgia. A Barn Owl banded in Courtney as a nestling 2 July 1999, was recovered some 160 km south in North Saanich, 2 April 2000 (Andrew Stewart pers. comm.). These two movements suggest that on occasion relatively long distant movements of Barn Owls can be expected on Vancouver Island.

Great Horned Owls are non-migratory, with the exception of the most northern populations, when irruptions often follow crashes of cyclic prey populations (Houston et al. 1998). The number of Great Horned Owls observed during the monitoring is likely explained as enumeration of the local breeding population, this is supported by the presence of a begging juvenile Great Horned Owl. The late begging behaviour of the juvenile suggests a late nest, however Houston et al (1998) notes that prey deliveries by adults to juveniles can continue into October. Interestingly, a prey delivery was observed at RPBO during first light on the morning 26 October.

It is thought that there were more Great Horned Owls in the area than estimated by the recording of vocalizations. Great Horned Owls were often seen from the access road as crews traveled to and from the study area, these birds were within kilometers from the monitoring site, but were far enough away to be missed by the monitoring. On a number of occasions Great Horned Owls were observed perching silently while other individuals vocalized in the distance, this suggests that the recording of vocalization of this species under estimated the true number present.

The Barred Owl was first recorded in British Columbia in 1943 at Liard Crossing (Munro and Cowen 1947). Since this time, this species has increased it’s range southward in British Columbia and currently the Barred Owl is relatively common on Vancouver Island. As with the Great Horned Owl, Barred Owls likely breed at Rocky Point and all of the observations of this species could be of individuals from a single-family group. Campbell et al. (1990) suggests that Barred Owls do undergo a northern withdrawal. It is thought that the number of Barred owls observed at RPBO is in part the result of an influx of this species.

The concentration of owls and the finding of predated individuals suggest that a dynamic predator prey interactions are being played out. It is possible that Barred Owls are congregating in the area to hunt the influx of Northern Saw-whet Owls. This may also be true for the Great Horned Owls or the local population of Great Horned Owls are targeting Barred Owls. On the 21 September a Great Horned Owl was seen attempting to kill a Barred Owl. The interaction continued for approximately 20 minutes until the Great Horned Owl was flushed off of the Barred Owl by the observer, who was attempting to photograph the two birds. The Barred Owl flew away, with the Great Horned Owl in pursuit (Ann Nightingale pers. comm.). It should be noted that there was not an organized search for prey remains and that all of the dead owls were found by chance.

Although present in the area, the monitoring methodology failed to detect Northern Pygmy-owl. The lack of detections of this species could be explained by few individuals being present in the area and/or individuals present in the area were not vocal. It is also possible that the timing of the monitoring was suitable for this species. The subspecies of Northern Pygmy-owl on Vancouver Island, Glaucidium gnoma swarthi is endemic to Vancouver Island (Campbell et al. 1990) and is provincially Blue Listed (CDC 2002). Seasonal movements of Northern Pygmy-owl in British Columbia have been noted by Campbell et al. (1990). Although mass movements of this species is unlikely to occur at RPBO, given the status of the population on Vancouver Island, an effort to develop suitable monitoring methodologies for RPBO should be undertaken. A possible starting point to achieve this task would be to experiment with playing Northern Pygmy-owl vocalizations through the audiolure in the late afternoon until dusk.

Western Screech-owls have been recorded at RPBO in the past and are thought to breed in the general area surrounding the observatory. However, Western Screech-owl was not recorded this year at RPBO. It was expected that monitoring methodology would at the very least elicit vocalizations and likely capture some Western Screech-owls. Western Screech-owls respond readily to Northern Saw-whet Owl vocalizations on Vancouver Island during the breeding period (Matkoski 1997, Manley 1999) and the playing of Northern Saw-whet Owl vocalizations does result in the capture of Eastern Screech-owls (Otus asio) and Boreal Owls (Aegolius funereus) at banding stations in the Great Lakes region and the east coast of North America.

The Western Screech-owl appears to be undergoing a range withdrawal on southern Vancouver Island (pers. obs.) and it is possible that this species no longer occurs at RPBO and surrounding areas.

The number of Northern Saw-whet Owls observed on the project is unprecedented in British Columbia. The Canadian Banding Office reports 288 Northern Saw-whet Owls banded in British Columbia between 1956 and 2001. At least 30 Northern Saw-whet Owls are known to have been banded on other projects in British Columbia during 2002, given this, the 210 banded at RPBO now represents 40% of all banding records for this species in the province.

Were the numbers of Northern Saw-whet Owls observed at RPBO during the fall of 2002 the result of an irruption leading to a fall invasion of this species on southern Vancouver Island? Perhaps, irruptions in the fall of Northern Saw-whet Owls have been well documented in eastern North America (Brinker et al. 1997). In British Columbia two likely Northern Saw-whet Owl irruptions have been noted, although details are scanty. The first occurrence was noted by Munro and Cowen (1947), "Occasionally, as in 1927, an invasion of southern localities occurs", Munro and Cowen then sight 15 winter records for the province spanning from 1895-1937, of which 6 records are from 1927. The second possible fall invasion occurred on southern Vancouver Island in 1950. Guiguet (1950) noted five Northern Saw-whet Owls were reported to the Provincial Museum between the 14-19 October; three of these reports involved owls being captured alive by residents in Sooke and Victoria. Since 1994, 12 Northern Saw-whet Owls have been banded at RPBO during the daytime passerine banding (Table 3). The number of Northern Saw-whet Owls banded at RPBO has varied annually from none to three, and this is likely representative of annual fluctuations in Northern Saw-whet Owls moving through the area. If the fall of 2002 was an irruption year for Northern Saw-whet Owls on Vancouver Island, it is likely that the number of this species banded during the day would increase correspondingly. However, only one Northern Saw-whet Owl was banded during the day at RPBO during the fall of 2002. It is likely that the number of Northern Saw-whet Owls observed at RPBO during the fall of 2002 was part of a normal, annual influx of this species.

Table 3. Occurrences of Northern Saw-whet Owls banded during daytime passerine banding at Rocky Point Bird Observatory between 1994-2002. Daytime passerine banding is terminated by the third week of October.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Are the Northern Saw-whet Owls at RPBO crossing over the 18 km Strait Juan de Fuca to Washington State? This can only be answered by band encounters and recoveries in Washington State The stopover times determined through the recapture of Northern Saw-whet Owls were relatively short and suggest that the owls were not remaining at RPBO for more than 24 hours. If the movement of these owls was simply altitudinal, with the owls moving from higher breeding elevations to lower wintering elevations, it should be expected that some of the owls would be recaptured on the following evening or even the following weekend, this was not the case.

The fall movement of Northern Saw-whet Owls at RPBO has potential management implications regarding the timing of spring inventories for this species. It is likely that a movement similar to the movement of Northern Saw-whet Owls observed in the fall at RPBO occurs during an undetermined time in the spring. Inventories using call playback to estimate breeding densities conducted during these movements would likely record vocalizing Northern Saw-whet Owls in transit. These potential false-positives could bias results causing a number of false conclusions ranging from the misidentification of suitable breeding habitat to masking local population declines. This information gap should be addressed and the best way would be to increase nest box programs to document local nesting chronology, coupled with spring migration monitoring efforts similar to the fall monitoring described in this document. At this time, biologists conducting inventories that include Northern Saw-whet Owls on Vancouver Island should be aware that this species maybe partly migratory and should consider this during the planning stages of future inventory projects and when analyzing results.

A number of authors have described the increase in capture rates of Northern Saw-whet Owls with the use of the audiolure (Duffy and Matheny 1997, Erdman and Brinker 1997, Erdman et al. 1997, Evans 1997) The trapping methodology proved to be very effective for capturing Northern saw-whet Owls during the fall on Vancouver Island. The audiolure seemed to excite the owls, when the audiolure was turn off the owls struggled less in the nets and were less aggressive towards extractors. In an effort to reduce the amount of stress placed on the owls during extraction, the lure was turned off as soon as an owl was known to be in a net. Once the owl was removed from the trapping area, the audiolure was then turned on, often eliciting vocalizations from Northern Saw-whet Owls in the immediate area. The 60 mm mesh size is well suite for capturing this species, a small number of Northern Saw-whet Owls were seen bouncing out of the nets or freeing themselves when approached, but the vast majority of owls were well entangled. Given the large percentage of Northern Saw-whet Owls captured in the nets closest to the audiolure, it is recommended that nets be placed in a tight square or triangle around the audiolure.

There are two recognized subspecies of Northern Saw-whet Owl, Aegolius acadicus acadicus the widely distributed subspecies, and Aegolius acadicus brooksi an endemic to the Queen Charlotte Islands and thought to be non-migratory (Campbell et al. 1990, Cannings 1993). It was thought given the lack of knowledge on Northern Saw-whet Owl movements in British Columbia, that it would be prudent to become familiar with the A. a. brooksi subspecies. This familiarity was gained by examining skin specimens of both subspecies at the Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM). It was clear that the Northern Saw-whet Owls banded at RPBO did not resemble the skin specimens of A. a. brooksi and were in fact A. a. acadicus. Photographic comparisons of both A. a. brooksi and A. a. acadicus skins from the RBCM can be viewed in Appendix II.

The Nocturnal Owl Migration Monitoring Project was made possible by financial assistance from the Public Conservation Assistance Fund. Permission to access the study site was provided by the Department of National Defence.

The Rocky Point Bird Observatory is operated by a volunteer board of directors deeply commitment to conservation and the increase of ornithological knowledge. David Allinson (President) Colleen O’Brien (Vice President), Tom Gillespie (Treasurer), Denise Gubersky (Secretary), Rod Mitchell (Site Manager), Rick Schortinghuis (Volunteer Coordinator), Suzanne Beauchesne, Marilyn Lambert, Michael Porter, Ann Nightingale and Paul Levesque, have work tirelessly to ensure that RPBO is successful season after season.

Don Doyle enthusiastically supported the project since it’s conception and made a number excellent suggestions regarding the project and funding proposal. Suzanne Beauchesne and Tom Gillespie also reviewed and made recommendations to the funding proposal. Andy Stewart was instrumental to the project a number of ways from securing banding permits, ordering bands, technical assistance, to simple encouragement; Andy’s contributions can be seen in the project’s successes. Raymond Chow of Soltek Solar Energy Ltd. provided excellent advice on the project’s power source requirements and provided a perfectly match system. Ann Nightingale assisted with data management and producing the final banding schedule. Rod Mitchell created the project’s webpage and Tom Gillespie provided project administration. Jim Cosgrove of the Royal B.C. Museum provided access to the museum’s bird skins collection and Gary Kaiser helped locate the specimens.

Thanks go to Jukka Jantunen, Ann Nightingale, Laurie Savard, Rick Schortinghuis, Andy Stewart and David Woodward, for their help with extracting and banding owls. Finding experienced banders for the demanding, but rewarding 2 am to 5:30 am shift was a challenge, but luckily the project team included Colleen O’Brien!

Laurie Savard was present for 17 of the 19 nights of banding, working from dusk to dawn. Laurie was involved with most aspects of the project and her contributions are far too numerous to list. Thank you LJS.

The following people assisted with the field component of the project and contributed to over 800 hours of checking nets, recording data and trying to stay warm:

David Allinson, Sydney Allinson, Beverly Allinson, Nicole Ayotte, Brent Beach, Stephanie Blouin, Don Doyle, Ann Duncan, Sue Ennis, Jeremy Gatten, Robert Gowen, Denise Gubersky, Morgan Gubersky, Sean Hansen, Jukka Jantunen, Dave Kelly, Marilyn Lambert, Matthew Levesque, Paul Levesque, Joanne McDonald, Marcy McKay Cheryl Mackie, Rod Mitchell, Jessica Murray, Ann Nightingale, Collen O’Brien Ed Pellizzon Chris Saunders, Carol Savard, Laurie Savard, Neil Savard, Rick Schortinghuis, Sarah Shea, Andy Stewart, Irene Stewart, Laura Stewart, Brad Stewart, Jeremy Warren, David Woodward and Harlan Wright.

Bird Studies Canada 2002. www.bsc-eoc.org/bscmain.html. British Columbia Nocturnal Owl Survey, www.bsc-eoc.org/regional/bcowls.html

Bloom, P. H. 1987. Capturing and Handling Raptors. In B. A. Pendleton, B. A. Millsap, K. W. Cline and D. M. Bird, Eds. Raptor Management Techniques Manual. National Wildlife Federation, Sci. Tech. Ser. No. 10, Pp 93-123.

Brinker, D. F., K. E. Duffy, D. M. Whalen, B. D. Watts and K. M. Dodge 1997. Autumn Migration of Northern Saw-whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) in the Middle Atlantic and Northeastern United States: What Observations from 1995 Suggest. In Duncan J. R., D. H. Johnson and T. H. Nicholls, Eds. Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd International Symposium; 1997 February 5-9; Winnipeg, MB. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-190, Pp 74-89.

Campbell, R. W., N. K. Dawe, I. McT. Cowan, J. M. Cooper, G. W. Kaiser and M. C. E. McNall 1990. The Birds of British Columbia Vol. 2: Nonpasserines. Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria.

Cannings, R. J. 1993. Northern Saw-whet Owl (Aegolius acadicus). In Birds of North America, No. 42, Poole, A. and F. Gills Eds. Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, DC: The American Ornithologist’s Union.

CDC 2002. British Columbia Conservation Data Centre, BC Species Explorer srmwww.gov.bc.ca/atrisk/toolintro.html

Derbyshire, D. 1999. Migration Monitoring at Rocky Point, Fall 1999. Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Metchosin, BC.

Derbyshire, D. 2000a. A Report on Migration Monitoring at Rocky Point: Fall 2000. Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Metchosin, BC.

Derbyshire, D. 2000b. Field Protocol for Migration Monitoring at Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Version 1.3. Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Metchosin, BC.

Duffy, K. E. and P. E. Matheny 1997. Northern Saw-whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) Captured at Cape May Point, NJ, 1980-1994: Comparison of Two Techniques. In Duncan, J. R., D. H. Johnson and T. H. Nicholls Eds. Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd International Symposium; 1997 February 5-9; Winnipeg, MB. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-190. Pp 131-137.

Erdman, T. C., T. O. Meyer, J. H. Smith and D. A. Erdman 1997. Autumn Populations and Movements of Migrant Northern Saw-whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) at Little Suamico, Wisconsin. In Duncan, J. R., D. H. Johnson and T. H. Nicholls Eds. Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd International Symposium; 1997 February 5-9; Winnipeg, MB. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-190. Pp 167-172.

Erdman, T. C. and D. F. Brinker 1997. Increasing Mist Net Captures of Migrant Northern Saw-whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) with an Audiolure. In Duncan, J. R., D. H. Johnson and T. H. Nicholls Eds. Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd International Symposium; 1997 February 5-9; Winnipeg, MB. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-190. Pp 533-544

Evans, D. L. and Rosenfield, R. R. 1987. Remigial Molt in Fall Migrant Long-eared and Northern Saw-whet Owls. In: Nero, R. W., Clark, R.J., Knapton, R.J., Hamre, R. H., Eds. Biology and Conservation of Northern Forest Owls: Symposium Proceedings; 1987 February 3-7; Winnipeg, MB. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM — 142. Fort Collins, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest and Range Experiment Station: Pp 209-214.

Evans, D. L. 1997. The Influence of Broadcast Tape-recorded Calls on Captures of Fall Migrant Northern Saw-whet Owls (Aegolius acadicus) and Long-eared Owls (Asio otus). In Duncan, J. R., D. H. Johnson, & T. H. Nicholls, Eds. Biology and Conservation of Owls of the Northern Hemisphere: 2nd International Symposium; 1997 February 5-9; Winnipeg, MB. USDA Forest Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-190. Pp 173-174.

Gibson, C. G. 2001. Migration Monitoring At Rocky Point Bird Observatory in 2001. Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Metchosin, BC.

Guiguet, C. J. 1950. Saw Whet Owl at Victoria. Victoria Naturalist Vol.7: 55-56.

Houston, C. S., D. G. Smith and C. Rohner. 1998. Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus). In Birds of North America, No. 372, Poole, A. and F. Gills Eds. The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

Joy, J., L. Peterson, N. Winchester, A. Mackinnon, D. Meidinger, M. Kellner and J. Voller 1999. Coastal Montane Biodiversity Inventory, 1998/99. BC Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Campbell River, BC.

Matkoski, W. R. 1997. Nimpkish Owl Inventory, 1996 Annual Report. W. M. Resource Consulting, and Canadian Forest Products Ltd., Englewood Logging Division, Woss, BC.

Manley, D. 1999. Beaver Lodge Forest Lands Wildlife and Wildlife Habitat Inventory. BC Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Campbell River, BC.

Mico, M. and T. van Enter 2000. Campbell River Watershed Owl Survey, Year 2000. BC Hydro, Vancouver, BC.

Munro, J. A. and I. McT. Cowen 1947. A Review of the Bird Fauna of British Columbia. British Columbia. Provincial Museum Special Publication No. 2, Victoria, BC.

Pendergast, S. R. 2002. Campbell River watershed Owl Survey and Nest Box Initiation. Program. BC Hydro Bridge River/ Coastal Compensation Fund, Nanaimo, BC.

Project Owlnet 2002. http://www.projectowlnet.org/

Pyle, P. 1997. Identification Guide to North American Birds Part I. Slate Creek Press, Bolinas, CA.

Ross, S. and M. Eggen 1997. Owl Inventory in Clayoquot sound. Wilcon Wildlife Consulting Ltd. and BC Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Nanaimo, BC.

Setterington, M. 1998. Owl Abundance and Habitat in the Nimpkish Valley, Vancouver Island. Canadian Forest Products Ltd. and Axys Environmental Consulting Ltd., Victoria, BC.

Figure 7. Museum skins of Northern Saw-whet Owl subspecies, Aegolius acadicus acadicus and Aegolius acadicus brooksi. Rows A and B are of birds collected from the Queen Charlotte Islands and are A. a. brooksi. Birds collected during the fall in the Victoria area are seen in row C, these birds are A. acadicus acadicus. Skin specimens are from the Royal British Columbia Museum. Photograph: Laurie Savard

Figure 8. Skin specimens of Aegolius acadicus acadicus and Aegolius acadicus brooksi. Colour contrasts between A. a. acadicus (A and C) collected during the fall in the Victoria area, and A. a. brooksi (B and D) collected on the Queen Charlotte Islands. Skin specimens are from the Royal British Columbia Museum. Photograph: Laurie Savard

Figure 9. Ventral (A) and Dorsal (B) views of Aegolius acadicus brooksi. The rust hues are found throughout the plumage of A. a. brooksi. Skin specimens are from the Royal British Columbia Museum. Photograph: Laurie Savard